I enjoy police ingenuity and avoid traffic incidents, look for tigers and find green tea, cool off at altitude and see men with attitude.

Alongside the hawkers of souvenirs and sunglasses and socks who patrol Brigade Road, the tourists and touts and teens, a flood of vehicles pours down the hill, monitored by traffic police officers. They sport thick black moustaches (better than mine), chevrons on their shoulders like Boy Scouts, and wide white hats, jauntily turned up on one side. Their warning signs also have a jaunty twist. “Speed thrills but kills”, “Follow traffic rules and avoid blood pools”, “Every time you drink & drive, you lose choice to survive”. I heard of an even better one, “Stay Married! Divorce Speed!” (I described more traffic signs in 2007 here.) The police slogan “Don’t use mobile when mobile” was reinforced in Hyderabad by posters of a phone’s ear plug cords outlining a prostrate body, and a revolver with a cell phone for a grip.

www.bangaloretrafficpolice.gov.in lists toll free ambulance numbers. It has a key to traffic signs, including “Bullock carts prohibited”. And it highlights Bangalore’s growth: between 1997 and 2010, the number of buses increased from 1921 to 6113, and travel speed has dropped to 15 kmph during peak hours. 70% of Bangalore’s 4 million vehicles are two-wheelers. If riders aren’t struck by the stats – helmets reduce the risk of brain damage or death by 70% – they might be alarmed by the alliteration: “Hell or helmet – the choice is yours!” Most riders I’ve seen evidently choose the afterlife.

www.bangaloretrafficpolice.gov.in lists toll free ambulance numbers. It has a key to traffic signs, including “Bullock carts prohibited”. And it highlights Bangalore’s growth: between 1997 and 2010, the number of buses increased from 1921 to 6113, and travel speed has dropped to 15 kmph during peak hours. 70% of Bangalore’s 4 million vehicles are two-wheelers. If riders aren’t struck by the stats – helmets reduce the risk of brain damage or death by 70% – they might be alarmed by the alliteration: “Hell or helmet – the choice is yours!” Most riders I’ve seen evidently choose the afterlife.

Urging drivers to give way, the website warns, “If every one is jostling for advantage, the results is a traffic mess out of which no one can get out”. A most precise description. A friend aptly described driving here as “slow-paced aggressive osmosis” – weaving and squeezing through any gaps you can find. On one billboard a straight line of baby swans follows their mother: “No traffic police here. They drive in one lane – why can’t you?” On another is a line of marching penguins: “If they can follow lane discipline, why can’t you?”

I pondered these conundrums as we sped down an interstate highway at 120 kmph on Friday for a teachers’ weekend getaway three weeks into the course. Lane discipline fell short of the cygnets, and despite exhortations like “You have only one head – protect it”, many motorcyclists are without helmets. Wife and offspring often cling on too. Guys hang out the backs of trucks; painted on the rear bumper of one was “I love you but don’t kiss me”. The asphalt is not a pool table surface. Most days papers report road deaths and we saw one motorcyclist spilled, though unhurt. We were slightly reassured to learn our driver had been 14 years without an accident. After starting at 7am to avoid traffic, we stopped for a South Indian breakfast of donut-like vadas, balloon-like pooris, pancake-like dosas, and rice cake idlis, dipped in coconut chutney and spicy samba soup.

I pondered these conundrums as we sped down an interstate highway at 120 kmph on Friday for a teachers’ weekend getaway three weeks into the course. Lane discipline fell short of the cygnets, and despite exhortations like “You have only one head – protect it”, many motorcyclists are without helmets. Wife and offspring often cling on too. Guys hang out the backs of trucks; painted on the rear bumper of one was “I love you but don’t kiss me”. The asphalt is not a pool table surface. Most days papers report road deaths and we saw one motorcyclist spilled, though unhurt. We were slightly reassured to learn our driver had been 14 years without an accident. After starting at 7am to avoid traffic, we stopped for a South Indian breakfast of donut-like vadas, balloon-like pooris, pancake-like dosas, and rice cake idlis, dipped in coconut chutney and spicy samba soup.

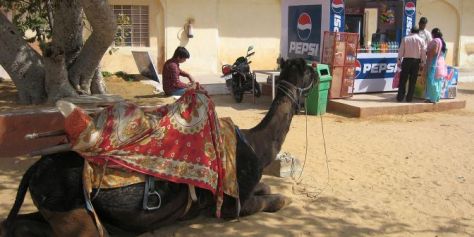

Back on the road, we passed dramatic rock outcrops before the fertile “green belt” of South India. We tried to identify the emerald crops: lower is rice, higher is sugar cane. Golden-olive palms, pelicans on a lake, white water buffalo pulling ploughs, bullocks hauling carts – driver aloft on a pile of grass, a lone donkey, a limping dog. Abandoned colonial bungalows. The advertisement “Coromandel King: for super cement” referred to India’s south-eastern Coromandel Coast, but reminded us of NZ’s Coromandel Peninsula. The road went through Mudumalai wildlife sanctuary, where we bumped over many judder bars and saw many signs announcing sloths and tigers. We looked for the latter among the groves of bamboo and eucalyptus trees, but saw only small monkeys, spotted deer and elephants with bells. People washed clothes in the river.

Then we climbed into the Nilgiri Hills. Hairpin bends became hair-raising when buses pushed past. As the temperature fell below 20oC, I opened the window and feasted my eyes on all the green: meadows of horses and sheep and cows, hills forested in pines, ferns that reminded me of home, rolling terraces of coffee or tea, the bushes cropped smooth with narrow channels between them, making a huge mosaic of verdant cobblestones.

Then we climbed into the Nilgiri Hills. Hairpin bends became hair-raising when buses pushed past. As the temperature fell below 20oC, I opened the window and feasted my eyes on all the green: meadows of horses and sheep and cows, hills forested in pines, ferns that reminded me of home, rolling terraces of coffee or tea, the bushes cropped smooth with narrow channels between them, making a huge mosaic of verdant cobblestones.

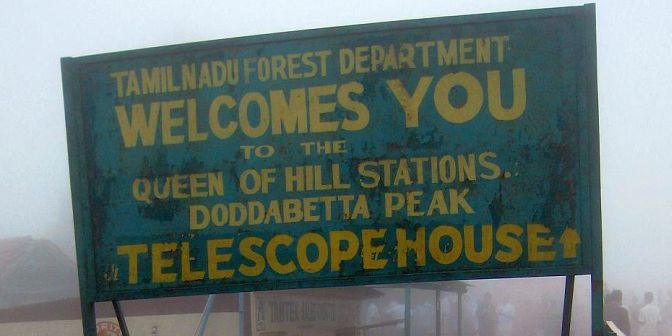

Our destination lay 300 km southwest of Bangalore: Udhagamandalam, or Ooty, the “Queen of Hill Stations”. At 2240 m asl, the temperature can drop to zero in winter, but was simply blissful in April. Ooty was an escape from summer meltdown for British aristocracy – thus the “Crown Baker, estd 1880”, and the nickname, “Snooty Ooty”. Houses are stacked up the terraced slopes, their walls painted lime, mauve, lemon, cream, while corrugated iron glinted on roof tops where the red tiles had fallen off. The valley floors are chequered with crops.

The highest point is Doddabetta at 2633m. No view at all from the lighthouse-shaped lookout that day, but I loved the mountain mist and wind and joined local teens in their summit victory dance, just before it poured. At the top, stalls sold woollen hats, scarves and binoculars, while orange splashes of carrots for sale brightened the wet drive down. Much more populated than NZ wilderness, but I backed into a prickly bush, turned, and saw the familiar yellow flowers of gorse. The Brits, bless them, must have imported it here too.

The highest point is Doddabetta at 2633m. No view at all from the lighthouse-shaped lookout that day, but I loved the mountain mist and wind and joined local teens in their summit victory dance, just before it poured. At the top, stalls sold woollen hats, scarves and binoculars, while orange splashes of carrots for sale brightened the wet drive down. Much more populated than NZ wilderness, but I backed into a prickly bush, turned, and saw the familiar yellow flowers of gorse. The Brits, bless them, must have imported it here too.

Ooty has a Christian school for expats that’s named for the Old Testament city of Hebron. Teacher Barbara’s sister studied there 70 years ago and we tracked down her sister’s records through three successive school sites. We stayed at another old institution, the Indian Sunday School Union. “People growers since 1876” read the sign on the gate. I woke to a dawn chorus of birds from raucous crows to tweeting sparrows, pulled on a light fleece for the first time in India, and stepped out into a brick-edged flower garden that reminded me of my grandmother’s in Christchurch. Walkers and joggers passed wearing beanies; people carried metal milk canisters clinking down the hill; women emerged onto flat house roofs to hang out their washing. On Sunday morning I heard church bells in the valley as well as Hindu temple chants. Ooty seems to combine an Indian town with an off-season ski resort. While some Indian chaos remains, it’s more relaxed and easier to tolerate in the cool, fresh air.

Ooty has a Christian school for expats that’s named for the Old Testament city of Hebron. Teacher Barbara’s sister studied there 70 years ago and we tracked down her sister’s records through three successive school sites. We stayed at another old institution, the Indian Sunday School Union. “People growers since 1876” read the sign on the gate. I woke to a dawn chorus of birds from raucous crows to tweeting sparrows, pulled on a light fleece for the first time in India, and stepped out into a brick-edged flower garden that reminded me of my grandmother’s in Christchurch. Walkers and joggers passed wearing beanies; people carried metal milk canisters clinking down the hill; women emerged onto flat house roofs to hang out their washing. On Sunday morning I heard church bells in the valley as well as Hindu temple chants. Ooty seems to combine an Indian town with an off-season ski resort. While some Indian chaos remains, it’s more relaxed and easier to tolerate in the cool, fresh air.

Like the police, Indian politicians are also more flamboyant. At Ooty, red and black flags waved for the visit of a local minister – I thought of pinching one for my Canterbury cousins: red and black are their rugby colours. Posters displayed the man in diverse poses. Formal in a business suit, casual in short sleeves, indigenous in a wraparound lungi, then brandishing a sceptre in a maharaja’s costume and flashing a huge jewel on his ring.

Politicians are widely despised as corrupt in India, but the army is more respected. Full page ads and billboards in Bangalore seek recruits: “Nation’s Pride”, “Be a winner”, “Arms you for life and a career” – “open to all castes and religions”. Ooty is still the base of the Madras Regiment, formed in 1748 and the oldest in the Indian army. We passed the Wellington Cantonment, with memorials to the 1960s-70s wars with Pakistan and China, and saw tight rows of soldiers at rifle training on a field below. In the overgrown cemetery behind the 1829 St Stephen’s church I found headstones for men from Fort St George, the Madras Artillery, the Bombay Cavalry, the Indian Navy, as well as many plaques for wives who died young.

Politicians are widely despised as corrupt in India, but the army is more respected. Full page ads and billboards in Bangalore seek recruits: “Nation’s Pride”, “Be a winner”, “Arms you for life and a career” – “open to all castes and religions”. Ooty is still the base of the Madras Regiment, formed in 1748 and the oldest in the Indian army. We passed the Wellington Cantonment, with memorials to the 1960s-70s wars with Pakistan and China, and saw tight rows of soldiers at rifle training on a field below. In the overgrown cemetery behind the 1829 St Stephen’s church I found headstones for men from Fort St George, the Madras Artillery, the Bombay Cavalry, the Indian Navy, as well as many plaques for wives who died young.

The cemetery is still used and a class from Hebron School was clearing undergrowth from a path. One headstone read “I have loved thee with an everlasting love”. Some plots had a small sign “reserved”. I wondered where in this wide world, and when in the everlasting Love’s embrace, a grave is reserved for me.

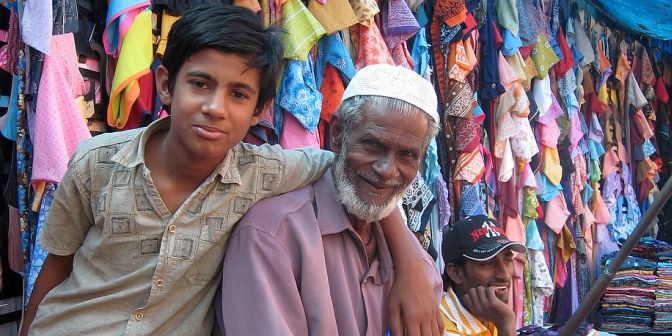

In New Delhi’s Connaught Place, a boy collared me, with agonized face and voice weakened by hunger, miming his need for food by putting his hand in his mouth. Older than usual, and unusually pushy, he seemed almost melodramatic. When he finally gave up following, I heard, loud and clear, in perfectly articulated English, “F you F-ing man”. Two passing women tittered, enjoying the performance. Not for nothing is the ring road called Connaught Circus: foreign clowns provide good sport.

In New Delhi’s Connaught Place, a boy collared me, with agonized face and voice weakened by hunger, miming his need for food by putting his hand in his mouth. Older than usual, and unusually pushy, he seemed almost melodramatic. When he finally gave up following, I heard, loud and clear, in perfectly articulated English, “F you F-ing man”. Two passing women tittered, enjoying the performance. Not for nothing is the ring road called Connaught Circus: foreign clowns provide good sport.