I remember the death of Christ and encounter the birth of a monkey god, cross barbed wire beset with flags and escape the clash of orange and green.

On Wednesday evening, sudden gusts whipped dust into my eyes and gloom descended over the Charminar, before the first rain I’d seen in weeks. I took shelter in a second-floor air-con café, grabbed an ice coffee and an easy chair overlooking the square, and enjoyed the show for an hour. As twilight deepened and the floodlights came on, the Charminar glowed purple, then rose, then yellow. Lightning flashed behind it, though I heard no thunder. The wind whipped flags. Pyramids of fruit gleamed under bare bulbs. Stall holders pulled tarpaulins over their carts and bag-sellers hurried off between showers. Looking at headlights to see whether rain was still falling, I noticed how few vehicles had their lights on.

The weather seemed to herald the gloom of Good Friday, when darkness fell over Jerusalem as Jesus was crucified. On Google I found Baptist Church Hyderabad was 10 minutes’ walk from my hotel, with a service at 11 am. It sounded ideal. Four policemen sat at the gate in front of rows of overflow seating under an awning. There was an English bulletin and worship songs from Hillsong Australia were playing as I entered. I also heard them in Korea and Kyoto years ago: the popular Protestant equivalent of the Roman Catholic mass in Latin. The familiar tunes warm the heart of the homesick traveller and I hummed along with almost a tear, but it’s a shame more peoples aren’t praising God in their own style and tongue.

And, in fact, they were here. The service turned out to be hours of incomprehensible Telegu. For each of Christ’s seven last words from the cross there was a full sermon, prayers and bracket of songs. Although I’d grabbed a pew under a fan, by 12:30 I’d emptied both my water bottles. I slipped outside, heard shouting at the end of the street, and found out why the police were there.

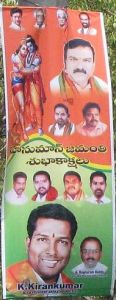

Young men zoomed past on motorbikes or an occasional truck. I switched my camera speed to ISO High. They waved bright orange or red pennants. The cloth triangles showed a black silhouette of a jumping monkey wielding a mace. The Christian Good Friday was also the Hindu Hanuman Jayanti, the birthday of the monkey god. In the Ramayana epic, Hanuman and his simian hordes helped the divine Lord Ram recover his kidnapped wife (see my post here). From a lamp post hung a political banner, showing party members alongside the blue-skinned Ram embracing Hanuman. When motorcyclists shouted “Jai Shri Ram”, or “Hail Lord Rama”, the crowd responded with the same words, especially to the mighty hollering of a zealot standing on a motorbike.

Young men zoomed past on motorbikes or an occasional truck. I switched my camera speed to ISO High. They waved bright orange or red pennants. The cloth triangles showed a black silhouette of a jumping monkey wielding a mace. The Christian Good Friday was also the Hindu Hanuman Jayanti, the birthday of the monkey god. In the Ramayana epic, Hanuman and his simian hordes helped the divine Lord Ram recover his kidnapped wife (see my post here). From a lamp post hung a political banner, showing party members alongside the blue-skinned Ram embracing Hanuman. When motorcyclists shouted “Jai Shri Ram”, or “Hail Lord Rama”, the crowd responded with the same words, especially to the mighty hollering of a zealot standing on a motorbike.

I remembered the headline in The Times of India at breakfast: “Blanket of Security for Rally Today”. “Heavy bandobust arrangements are in place” and “10K Cops Deployed”, including 32 battalions of Special Police and four companies of Rapid Action Force, with peace committee volunteers also on vigil. In British times the ruling Nizams were marked by religious tolerance, but Hyderabad has since become known as a riot-prone city. In 2010, Hindu flags in Muslim areas sparked stone pelting and communal clashes at the Hanuman rally, leading to several days of curfew. This year an inflammatory leader of a fundamentalist Hindu party was allowed to speak publicly.

I remembered the headline in The Times of India at breakfast: “Blanket of Security for Rally Today”. “Heavy bandobust arrangements are in place” and “10K Cops Deployed”, including 32 battalions of Special Police and four companies of Rapid Action Force, with peace committee volunteers also on vigil. In British times the ruling Nizams were marked by religious tolerance, but Hyderabad has since become known as a riot-prone city. In 2010, Hindu flags in Muslim areas sparked stone pelting and communal clashes at the Hanuman rally, leading to several days of curfew. This year an inflammatory leader of a fundamentalist Hindu party was allowed to speak publicly.

“Police is geared up to handle any situation proactively” assured the commissioner, with police pickets near mosques and churches “to prevent any untoward incident.” One building the size of a shed was encircled by coiled razor wire and covered in a tarpaulin. Through a crack I glimpsed green, the colour of Islam: it was a Muslim shrine.

Ebbing and flowing, the stream of flags on wheels seemed endless. Organisers had expected the bike rally to attract over 200,000 participants. They were officially requested “not to cover their faces and not to hide the vehicle registration numbers with stickers”. Many shops were keeping security roller doors down until after the Muslim Friday afternoon prayers. Further along the street, youths danced to pumping Hindu music. A lad waved a banner far longer than himself. Small plastic pockets of water were distributed to sweating devotees. No doubt many had downloaded the Hanuman ringtones advertised in the paper.

Traffic piled up behind police barricades on side streets and to get back to my hotel, I had to climb through barbed wire strands and weave through the gridlock. I recalled the Passover festival in Jerusalem two millennia ago, when the presence of Roman troops was pumped up to make sure religious excitement didn’t turn to revolution. The tensions between idol-worshipping Romans and monotheistic Jews were not unlike those between Hindus and Muslims here today.

Traffic piled up behind police barricades on side streets and to get back to my hotel, I had to climb through barbed wire strands and weave through the gridlock. I recalled the Passover festival in Jerusalem two millennia ago, when the presence of Roman troops was pumped up to make sure religious excitement didn’t turn to revolution. The tensions between idol-worshipping Romans and monotheistic Jews were not unlike those between Hindus and Muslims here today.

I read of the aftermath a few days later, once I was safely in Bangalore. There were a few jitters as the procession passed a mosque and a few Muslims with slogans, but no real trouble and the cops were relaxed. Later on, however, riots broke out. People were stabbed. Dead animals and dog parts were thrown into places of worship. For much of the week the old city around the Charminar where I’d been in the previous days was completely closed. Tourists were frustrated. Shops lost revenue. Residents were running out of medicine and milk.

O come the day when the Prince of Peace, killed in darkness at Easter and risen in new life, will complete his work and break down every wall of resentment, religion and race.