I visit mosques of the world and unearth relics of Mohammed; I collect a pantheon of cartoon gods and choose a winning goddess.

In between my encounters with fruits, flowers, and primal colours that make even Disney look tame (see previous post here), I found a vendor of Muslim devotional items. When I asked if he had calendars, he strode off. I almost lost him around a maze of corners, before reaching the Naaz Book Depot. It had racks of calendars, many designed by the owner on his PC. He bemoaned the decline in Arabic calligraphy. Few people have the patience to spend hours or months doing by hand what computers can print in minutes. When I said I was teaching English, he asked whether I taught calligraphy: he’d be my student. I admitted my ignorance of the art – Dad once compared my writing to a drunken spider staggering across the page – and asked which of his calendars sold the best.

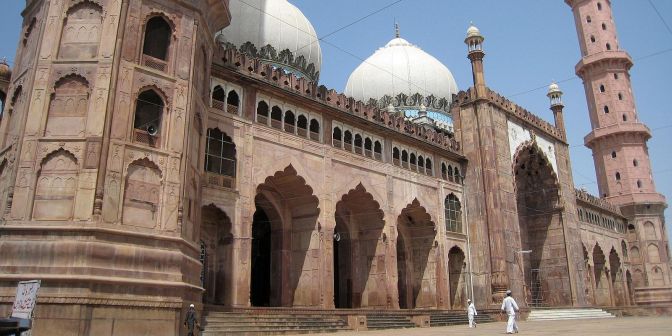

I bought two, both arranged by Western dates with the Muslim lunar days in small letters. My birthday this year was Rabi-ul-Awwal 30. Hindu, Christian and Muslim festivals are marked in Hindi, English and Urdu scripts. One calendar shows mosques on each page. January has an aerial night-time photo of Mecca. The concentric white rings of praying figures reminded me of raked sand in a Zen garden. Other months show an old khaki façade in East Turkistan, a bland concrete box in Canada, a mosque in Jakarta with blue batik patterns, and the “floating” mosque in Borneo. December gleamed with the Crystal Masjid in Malaysia, a fantasy of metallic domes and spires. The collection of shots gave me a sense of the worldwide community of Islam. On the rear of each page are the five daily prayer times in Mumbai, Hyderabad and Bangalore.

I bought two, both arranged by Western dates with the Muslim lunar days in small letters. My birthday this year was Rabi-ul-Awwal 30. Hindu, Christian and Muslim festivals are marked in Hindi, English and Urdu scripts. One calendar shows mosques on each page. January has an aerial night-time photo of Mecca. The concentric white rings of praying figures reminded me of raked sand in a Zen garden. Other months show an old khaki façade in East Turkistan, a bland concrete box in Canada, a mosque in Jakarta with blue batik patterns, and the “floating” mosque in Borneo. December gleamed with the Crystal Masjid in Malaysia, a fantasy of metallic domes and spires. The collection of shots gave me a sense of the worldwide community of Islam. On the rear of each page are the five daily prayer times in Mumbai, Hyderabad and Bangalore.

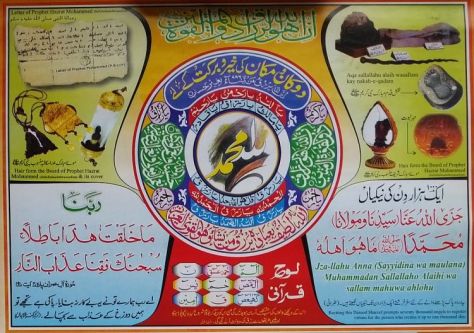

The second calendar has quarterly pages and is less orthodox. Instead of mosques it has pictures of relics: a rough-edged parchment letter written by Muhammad, the Holy Mantle of the Prophet Mohammed, the “protective case of the leather sandal of the Prophet Hazrat Mohammed”, and, in a lump of black granite, the footprint of Mohammed. The sword of Mohammed lies alongside its jewel encrusted sheath; jewelled reliquaries contain the tooth of Mohammed and soil from Mohammed’s grave. Something like black wool in a glass cylinder with golden caps is labelled hair from the beard of Mohammed. (Will anyone care to save my whiskers?) By way of variety, one page had a box and blouse from Fatima, daughter of Mohammed, with two items of clothing from the Shiite martyr Imam Hussain.

Each page has a saying of Mohammed from the Hadith. “One should be scared of death, so stand up when you notice a funeral”. “That nation will never be benefited which is owned and governed by a woman”. I didn’t ask my new acquaintance what he thought of Prime Minister Indira or Sonia Gandhi. But I shouldn’t mock, for “Backbiters will not enter Paradise”, and “those who do not show Mercy to others, Allah will never be Merciful to them.”

Each page has a saying of Mohammed from the Hadith. “One should be scared of death, so stand up when you notice a funeral”. “That nation will never be benefited which is owned and governed by a woman”. I didn’t ask my new acquaintance what he thought of Prime Minister Indira or Sonia Gandhi. But I shouldn’t mock, for “Backbiters will not enter Paradise”, and “those who do not show Mercy to others, Allah will never be Merciful to them.”

The centre of each page is a circular swirl of colour and calligraphy. I suspect one page is the 99 names of God; page 4 resembled a Tibetan Buddhist Mandela. I was intrigued by the promises appended to Arabic invocations, which struck me as more superstitious than Islamic. “Whoever recites this Darood 80 times after Asar prayer on Friday his 80 years of sins are forgiven by the grace of Allah.” Christ said he could call on 12 legions of angels (Matthew 26:53) or 72,000 in Roman military terms. With a few repetitions you too can engage a similar count of heavenly aides. “Reciting this Darood Shareef prompts seventy thousand angels to register virtues for the person who recites it up to one thousand day.”

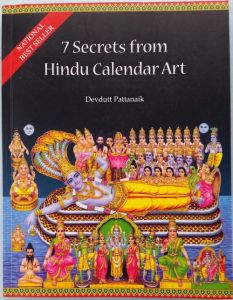

Equipped with Muslim calendars, I went in search of the Hindu equivalent. I’d seen garish calendars of gods hanging in shops, offices, hotels, and houses and had just bought a book that explains their meanings: Seven Secrets from Hindu Calendar Art. I drew a blank on calendars, but around another corner two men were mounting pictures of gods in gold-painted frames. Larger reproductions were embossed with glitter. I asked to buy one of each smaller, non-sparkling print, which gave me 18 vivid icons of the most common gods, as bright as Walt Disney cartoons and spunkier than American superheroes.

Equipped with Muslim calendars, I went in search of the Hindu equivalent. I’d seen garish calendars of gods hanging in shops, offices, hotels, and houses and had just bought a book that explains their meanings: Seven Secrets from Hindu Calendar Art. I drew a blank on calendars, but around another corner two men were mounting pictures of gods in gold-painted frames. Larger reproductions were embossed with glitter. I asked to buy one of each smaller, non-sparkling print, which gave me 18 vivid icons of the most common gods, as bright as Walt Disney cartoons and spunkier than American superheroes.

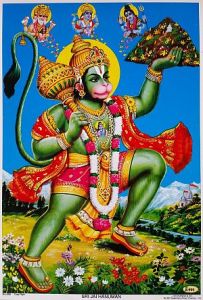

Monkey-god Hanuman, green as the Incredible Hulk, strides across a mountain meadow. One hand wields a golden mace studded with rubies and emeralds; the other holds a forested hill aloft like a waiter carrying a plate. (He had been dispatched to get a certain healing herb that grows on this sacred hill. His botanical knowledge falls short of his strength so he brings the whole mountain instead.)

Monkey-god Hanuman, green as the Incredible Hulk, strides across a mountain meadow. One hand wields a golden mace studded with rubies and emeralds; the other holds a forested hill aloft like a waiter carrying a plate. (He had been dispatched to get a certain healing herb that grows on this sacred hill. His botanical knowledge falls short of his strength so he brings the whole mountain instead.)

Elephant-headed Ganesh sits on a yellow lotus, belly bulging beneath his trunk. His right tusk is broken off. He was the scribe of the epic Mahabharata and his nib broke as he was writing it down. Dictation continued so fast he had to grab this tusk for a pen. His mouse crouches at his feet and nibbles on a sweet. Ganesh is the son of blue-skinned Shiva, who sits on a Himalayan glacier with a trident, a cobra coiled around his neck and the river Ganges cascading from his knotted hair (see my post on Shiva here). The god Vishnu reclines on the multi-hooded cosmic serpent, or poses in his incarnation with a lion’s head (see my post on Vishnu’s avatars here).

Vishnu’s consort Lakshmi, goddess of wealth, sits in the lotus position on a pink lotus and pours out a shower of gold coins – businessmen love her. My set lacked the gory gals who are favourites with feminists: Durga riding a tiger with abundant arms waving fearsome weapons, or black-skinned Kali with a necklace of skulls, tearing out a man’s intestines.

Of all the female deities, whether sexy or scary, my babe would have to be Saraswati. She’s the goddess of learning and the arts and I did get a picture of her. She wears a red blouse and modest white sari. One hand holds a book, a second fingers meditation beads, while her other two arms play the stringed veena, a sort of long bulbous lute. For a portrait of Saraswati that’s less garish and Mickey Mouse, I bought a card at a Bangalore art gallery. Ravi Varma was influenced by European painting, and he seats Saraswati in an impressionist scene of lotus blossoms on a pastel lake (1896).

Of all the female deities, whether sexy or scary, my babe would have to be Saraswati. She’s the goddess of learning and the arts and I did get a picture of her. She wears a red blouse and modest white sari. One hand holds a book, a second fingers meditation beads, while her other two arms play the stringed veena, a sort of long bulbous lute. For a portrait of Saraswati that’s less garish and Mickey Mouse, I bought a card at a Bangalore art gallery. Ravi Varma was influenced by European painting, and he seats Saraswati in an impressionist scene of lotus blossoms on a pastel lake (1896).

I travelled second class AC, on the upper bunk. With my bag alongside my feet, I just had room to sit or stretch out; in third class which is three tier I’d be hunchbacked. Towels, sheets and blankets are provided on the blue vinyl mattress. With mesh pockets to hold bottle, book and glasses, and your own reading lamp, once you draw the curtain it’s a cosy little shelter. Vendors move along the carriage droning “pani water pani water” – chilled water bottles, “chai coffee chai coffee” – Western teabag or coffee, “masala tea” – the Indian brew, “tomato soup” – with croutons. Each is poured from a thermos into a small paper cup for five rupees, about ten cents. There are cartons of juice, punnets of yoghurt, packets of chips; and omelette, “veg” or “nonveg” meals. I bought the vegetarian for Rs 50. Like an aeroplane meal, it comes in a tin foil tray: three chapattis, vegetables, runny yellow dal that almost spilled until I spooned it onto the rice. I inserted my ear plugs, and had more sleep than I did on trains in 2007.

I travelled second class AC, on the upper bunk. With my bag alongside my feet, I just had room to sit or stretch out; in third class which is three tier I’d be hunchbacked. Towels, sheets and blankets are provided on the blue vinyl mattress. With mesh pockets to hold bottle, book and glasses, and your own reading lamp, once you draw the curtain it’s a cosy little shelter. Vendors move along the carriage droning “pani water pani water” – chilled water bottles, “chai coffee chai coffee” – Western teabag or coffee, “masala tea” – the Indian brew, “tomato soup” – with croutons. Each is poured from a thermos into a small paper cup for five rupees, about ten cents. There are cartons of juice, punnets of yoghurt, packets of chips; and omelette, “veg” or “nonveg” meals. I bought the vegetarian for Rs 50. Like an aeroplane meal, it comes in a tin foil tray: three chapattis, vegetables, runny yellow dal that almost spilled until I spooned it onto the rice. I inserted my ear plugs, and had more sleep than I did on trains in 2007.