I breakfast on spicy crêpe, follow my nose to market, and cook up Indian aromas; I practice Hindi and bypass heatstroke, dodge dentists and float through floral fantasies.

I began my penultimate Saturday in Bangalore at the Mavalli Tiffin Rooms, where steam from metre-wide vats of sambar clouded my camera lens as I entered. It’s been a popular spot since 1924 and the walls are lined with black and white photographs. It was the first fast food eatery to serve 21,000 customers in seven hours, and I had to put my name down to queue for one of the faux marble tables. I ordered the classic South Indian breakfast of masala dosa: a thin pancake – sometimes over a foot long – wrapped around a yellow potato-onion curry, with side bowls of cooling coconut and spicy red chutney.

I began my penultimate Saturday in Bangalore at the Mavalli Tiffin Rooms, where steam from metre-wide vats of sambar clouded my camera lens as I entered. It’s been a popular spot since 1924 and the walls are lined with black and white photographs. It was the first fast food eatery to serve 21,000 customers in seven hours, and I had to put my name down to queue for one of the faux marble tables. I ordered the classic South Indian breakfast of masala dosa: a thin pancake – sometimes over a foot long – wrapped around a yellow potato-onion curry, with side bowls of cooling coconut and spicy red chutney.

I made way for the next customer, stepped outside, and traversed a very different suburb from my previous weekend in the swept-up city centre of Nike and McDonald’s. Here in one block were Birla Tyres and Raja Tools, the Hanuman Auto Centre, Sagar Radiators and Sita Tractor. Hindu deities meet greasy mechanics. I passed the Eastern Compressors and Pneumatics, Citizen Clutch Center, and Motor Cycle Shrinagar. A poster over Studds Helmets and Accessories showed a rider performing a handstand and motorbike wheelie, while the Automotive Sales Corporation rhymed, “If you are making a bus, you will definitively need us”. It was tempting, but I decided not to build a bus just now and moved on towards Bangalore’s City Market.

Although I carry map and compass, I could have just followed my nose. Deepening piles of rotting produce spelt paradise for goats and cows. A barefoot holy man with dreadlocks reverently touched one cow, then brought his hand to his forehead. A kitten meandered past with diseased eye and missing patches of hair. I stepped aside for a woman sweeping rubbish onto sackcloth. Something didn’t seem right and I took another look: her sandaled feet each had six toes. Further up the road, I squeezed between a stone wall and a truck delivering vegetables – the driver said he came every day from outlying farms. Tomatoes were piled into stacks of square plastic crates and the ground was slippery with red pulp. A front-loader cleared a path through the refuse.

Although I carry map and compass, I could have just followed my nose. Deepening piles of rotting produce spelt paradise for goats and cows. A barefoot holy man with dreadlocks reverently touched one cow, then brought his hand to his forehead. A kitten meandered past with diseased eye and missing patches of hair. I stepped aside for a woman sweeping rubbish onto sackcloth. Something didn’t seem right and I took another look: her sandaled feet each had six toes. Further up the road, I squeezed between a stone wall and a truck delivering vegetables – the driver said he came every day from outlying farms. Tomatoes were piled into stacks of square plastic crates and the ground was slippery with red pulp. A front-loader cleared a path through the refuse.

Some months ago a friend asked for a sample of the aroma of India. After endless experimentation, I have created the Titheridge Smell India At Home recipe, patent pending, to share such experience. First assemble the following ingredients behind an old car or lawnmower with a dirty-burning engine: matches, perfume, a stick of incense, fragrant flowers, dry leaves, rotting compost, a fresh steaming Indian curry, a fresh steaming cow pat. Then start the motor, spray the perfume, light the incense stick and burn the leaves. Swallow a handful of curry, close your eyes and breathe deeply. Voilà! You have the olfactory mélange of an Indian market, without the cost of an airfare. For that extra dash of aromatic authenticity, first go for a run so your shirt is soaked in sweat, then smash open a coconut and pee on the ground.

Some months ago a friend asked for a sample of the aroma of India. After endless experimentation, I have created the Titheridge Smell India At Home recipe, patent pending, to share such experience. First assemble the following ingredients behind an old car or lawnmower with a dirty-burning engine: matches, perfume, a stick of incense, fragrant flowers, dry leaves, rotting compost, a fresh steaming Indian curry, a fresh steaming cow pat. Then start the motor, spray the perfume, light the incense stick and burn the leaves. Swallow a handful of curry, close your eyes and breathe deeply. Voilà! You have the olfactory mélange of an Indian market, without the cost of an airfare. For that extra dash of aromatic authenticity, first go for a run so your shirt is soaked in sweat, then smash open a coconut and pee on the ground.

What you won’t experience at home is being so often hailed “Your country, sir? Your name?” that it’s hard to note your surroundings. So many people asked for photos I feared my battery would run out. One guy posed with a Jurassic Park T-shirt and cane basket on his head; two reclined on sacks of onions under a red awning. A skinny bloke with a short lungi cloth wrapped around his waist leaned against boxes of Kashmiri Fresh Apples, while others sold emerald capsicums or lime peppers, mottled green-orange mangos or small sweet bananas. Shiny scale pans were balanced by rusty hexagonal weights.

What you won’t experience at home is being so often hailed “Your country, sir? Your name?” that it’s hard to note your surroundings. So many people asked for photos I feared my battery would run out. One guy posed with a Jurassic Park T-shirt and cane basket on his head; two reclined on sacks of onions under a red awning. A skinny bloke with a short lungi cloth wrapped around his waist leaned against boxes of Kashmiri Fresh Apples, while others sold emerald capsicums or lime peppers, mottled green-orange mangos or small sweet bananas. Shiny scale pans were balanced by rusty hexagonal weights.

As the heat increased I also feared my water would run out, far from middle-class tourist terrain and 7-11 superettes. I needn’t have worried. Akbar was so delighted I knew of Emperor Akbar the Great he gave me a bottle of Indian “Fanta” from a friend’s shop. He refused payment, proving that the study of history does have pragmatic value. I passed a woman ladling cold drinks I wouldn’t trust from bulbous clay jars on a cart, then a guy in a singlet soaping and sluicing down his pavement. He grabbed my hand, pulling me aside. “Wait! Wait!” He sat me on a chair and shot off. I’d just wiped off the soap suds when he reappeared with a bottle of Thumbs-up, the local Coke. I don’t much like its liquorice tang.

In a shady side lane with more solitude, flowers were strung over apartment doors. Drying saris rippled down from balconies like crimson and emerald waterfalls. I sketched the kolam patterns on the step where I was sitting, traced out by women with a fistful of rice powder after sweeping their threshold at dawn. These ones resembled a white Celtic knot; others are like multi-coloured flowers. Most show a mathematical symmetry, like drawings from the Spirograph cogwheels I had as a boy.

A slim young chap with black beard sat on a scales platform – the LED display read 53 kg. He invited me over, and was excited to find I could speak some Hindi. Even a little makes a lot of friends. A Muslim himself, he introduced his best friend, a Christian, then Hindu comrades, showing off his country’s inclusiveness. He joked that one friend was the “Shaitan” (Satan) of Bangalore, drumming on the bare belly of a corpulent mate. Another brandished an iron hook with a cow-horn handle, which he said he used to carry sacks weighing up to 150kg. At last their chai-wallah pal arrived with a stack of glasses and thermos of steaming tea, for my third complementary beverage that day.

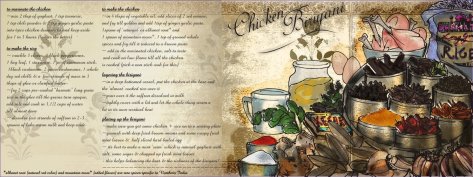

For lunch, I cooled off under a fan with my favourite Muslim dish of mutton biryani: spicy yellow basmati rice with tender meat, and a bowl of purplish eggplant-and-tomato curry. I amused myself while waiting by identifying menu items in the “culinary reader” of my Lonely Planet phrasebook.

Back outside was a stand of pirated DVDs: the vendor offered me “Nauty Movie: English Romantic Video”. Other stalls flaunted photos of dentists holding open their victims’ mouths, and vampire-like close-ups of jagged incisors in blood-red gums. On their counters were neat rows of molars in glass cases, assorted pink dentures and torture instruments laid out for road-side extractions.

Back outside was a stand of pirated DVDs: the vendor offered me “Nauty Movie: English Romantic Video”. Other stalls flaunted photos of dentists holding open their victims’ mouths, and vampire-like close-ups of jagged incisors in blood-red gums. On their counters were neat rows of molars in glass cases, assorted pink dentures and torture instruments laid out for road-side extractions.

A man in a long purple shirt was combing his chest-length black beard near a booth with shelves of Muslim caps and perfume bottles. The owner dabbed some on my shoulders and lapels. I watched a woman praying at a small Sufi shrine, the tomb covered in red cloth and white jasmine with scores of small padlocks fastened to the green bars of the gate. She held an open padlock and I wondered what she was asking for, but I gave up waiting for her to fasten it on. Then back through the market farmyard – its aroma overpowered the perfume on my collar. Pyramids of apples and oranges and limes, then a stack of pomegranates, the top row cut open like stars or flowers. I declined a grubby handful of the crimson seeds, and entered the breezy but gloomy market building.

Cones of powder as bright as a baby’s toys in yellow, pink and red. I was nervous I’d jostle them in the crowd. Pedal-driven sewing machines. A shop of farming implements displayed scythes and sickles, then two wooden coffins leaning against the wall.

Cones of powder as bright as a baby’s toys in yellow, pink and red. I was nervous I’d jostle them in the crowd. Pedal-driven sewing machines. A shop of farming implements displayed scythes and sickles, then two wooden coffins leaning against the wall.

Men and women on the floor were pulling petals or stems off flowers of all colours, threading them into chains or tossing them into baskets. Some were arranged on frames of lettering with wedding felicitations, or into a deity’s outline, or onto papier-mâché shrines. A man announced I was from NZ and a young woman rose from the knee-high drifts of blossoms to tug my hand, saying something like “take me with you”. I was startled. A middle-class woman might shake hands, but I’d never been touched – or hardly addressed – by one in the market, except for beggars pulling my sleeve.

Men and women on the floor were pulling petals or stems off flowers of all colours, threading them into chains or tossing them into baskets. Some were arranged on frames of lettering with wedding felicitations, or into a deity’s outline, or onto papier-mâché shrines. A man announced I was from NZ and a young woman rose from the knee-high drifts of blossoms to tug my hand, saying something like “take me with you”. I was startled. A middle-class woman might shake hands, but I’d never been touched – or hardly addressed – by one in the market, except for beggars pulling my sleeve.

Escaping the flirtatious florist, I moved towards the market’s inner sanctum. Indian idols are often smothered in thick floral garlands; some are all of the same flower species, some have alternating stripes like blown-up football scarves. In the central courtyard, lit by sunlight through the plastic roof, garlands were coiled in cane baskets a metre wide. Salesmen drew them out to measure arm-lengths for customers. Seen from the balcony above, each basketful resembled a huge blossom, or a giant pin cushion, or perhaps a pot of gluggy paint. On the ground, swimming through the ocean of colour, it was a camera battery-flattening visual overload, the same vibrant explosion I experienced here in 2007 (see here).

Escaping the flirtatious florist, I moved towards the market’s inner sanctum. Indian idols are often smothered in thick floral garlands; some are all of the same flower species, some have alternating stripes like blown-up football scarves. In the central courtyard, lit by sunlight through the plastic roof, garlands were coiled in cane baskets a metre wide. Salesmen drew them out to measure arm-lengths for customers. Seen from the balcony above, each basketful resembled a huge blossom, or a giant pin cushion, or perhaps a pot of gluggy paint. On the ground, swimming through the ocean of colour, it was a camera battery-flattening visual overload, the same vibrant explosion I experienced here in 2007 (see here).

As I headed through this mechanics’ paradise, as innocent as Adam, I was hailed by a guy in jeans with three cane baskets. He placed them on the ground, and opened each one: on yellow clothes were coiled black cobras! He held them up in his hands saying “photo photo”, then pretended to charm his serpents by waving a bulbous pipe with a few random toots, then demanded 200 rupees. I gave him 30. Judging by his satisfied appearance and an on-looker’s grin, I was probably ripped off by Indian standards, but it was all so fast and I feared to offend a handler of live snakes.

As I headed through this mechanics’ paradise, as innocent as Adam, I was hailed by a guy in jeans with three cane baskets. He placed them on the ground, and opened each one: on yellow clothes were coiled black cobras! He held them up in his hands saying “photo photo”, then pretended to charm his serpents by waving a bulbous pipe with a few random toots, then demanded 200 rupees. I gave him 30. Judging by his satisfied appearance and an on-looker’s grin, I was probably ripped off by Indian standards, but it was all so fast and I feared to offend a handler of live snakes.